Shildon, County Durham

Shildon Coal Drops

Last Updated:

9 Oct 2023

Shildon, County Durham

This is a

Coal Drops

54.626216, -1.638114

Founded in

Current status is

Extant

Designer (if known):

Listed Grade II*

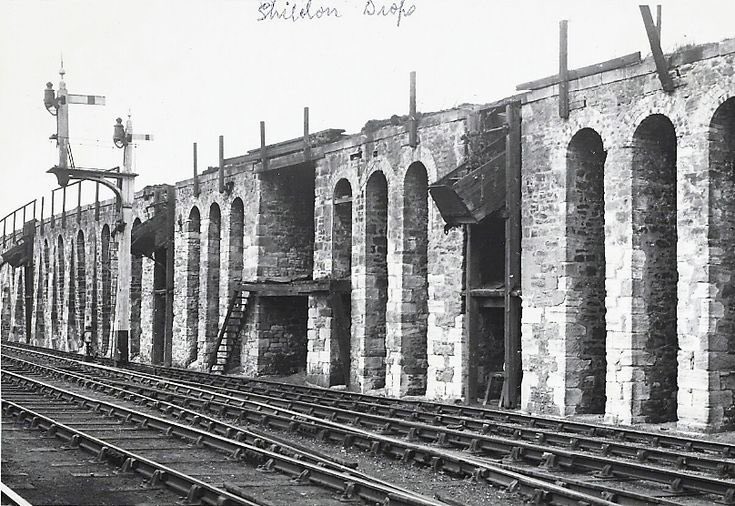

These are the first purpose built tender coal drops on the planet, built 1846 for the Stockton and Darlington Railway to refuel locomotives. Coal held in a wagon would fall down the chute into a waiting tender. Before this it was shovelled in by hand, vastly speeding up the process. Though there are earlier drops, namely at Oakwellgate at Gateshead and along the Stanhope and Tyne Railway, these are known to be the first drops specifically to add coal to a tender. A tender is where the coal is stored behind the locomotive engine.

The marshalling yard at Shildon was huge and speed was key to distribute coal quickly to Darlington and Middlesbrough. Thanks to it being a central junction between the Stockton & Darlington Railway, the Surtees Railway and the Black Boy Colliery Railway it was also a site with an abundance of coal at hand, making it an easy decision to erect the drops here.

It was the first known attempt to mechanise the process which was time consuming and inefficient, and meant yardmen could focus their attention elsewhere.

Though the chutes themselves no longer survive, the stone structure does and is a key part of the Shildon railway heritage attraction. With this said, some iron brackets and fittings do survive embedded in the masonry.

Heritage services for the National Railway Museum will potentially be running past here again as of 2023.

Listing Description (if available)

The Ordnance Survey maps above illustrate the Soho Works are from the mid 19th century through to the turn of the 1900s. The coal drops are illustrated, but not labelled.

The layout is very much retained through the decades, but gets gradually more dense with the inclusion of Shildon Colliery and the Marshalling yards to the east. The village of New Shildon itself also expands significantly with the growth of industry in the town, complete with another colliery near the Shildon Brickworks. By the 1890s Shildon was outgrowing itself. The Sebastapol roundhouse in the west of the village was replaced with Shildon Wagon Works.

This map was published in 1924 but was surveyed just before WWI. Little had changed since the 1890s, but further amenities can be spotted for the people of Shildon as they started to strive for a better standard of living outside of work. A golf course can be seen, alongside a number of churches. Just outside of view there was a football ground at Shildon Wagon Works.

The coal drops were still operating at this time.

The Shildon Coal Drops in 2023

The drops in 1932. Source: Darlington Railway Museum

The drops next to wooden semaphore signals. Undated but picture quality indicates 20s-30s. Source: Durham University